Math has never been cooler than in the presence of Ed Thorp. A dreary subject matter for most, this wild and abstract dance of the numbers took shape and scope on the blackjack table as the self-declared “man who beat the dealer” learned its moves, along with all the twists and twirls of gambling odds and roulette probabilities, and declared war on the big-money empires.

Why did Las Vegas ban Edward Thorp from entering the premises of its gambling establishments, with one, the professor claims, even resorting to drugging him? Why was this brilliant wandering intellect branded as an undesirable?

Because he was no cheater, but no loser either. And because, through his algebraic odyssey, he broke the myth of the “unbeatable casino.”

His card-counting technique and, later, the first wearable computer to have ever been invented and tested against the roulette, constituted breaches of casino etiquette and digital enhancements that Las Vegas wasn’t ready to fight yet.

Ed Thorp’s Winning Philosophy in 3 Lessons

At 30 years old, he beat the casinos.

At 37, he started the first quant hedge fund that would net $273 million in the span of two decades.

At 58 years of age, he cracked Bernard Madoff’s Ponzi Schemes almost 17 years before the newspaper headlines exposed the largest fraud at the turn of the century.

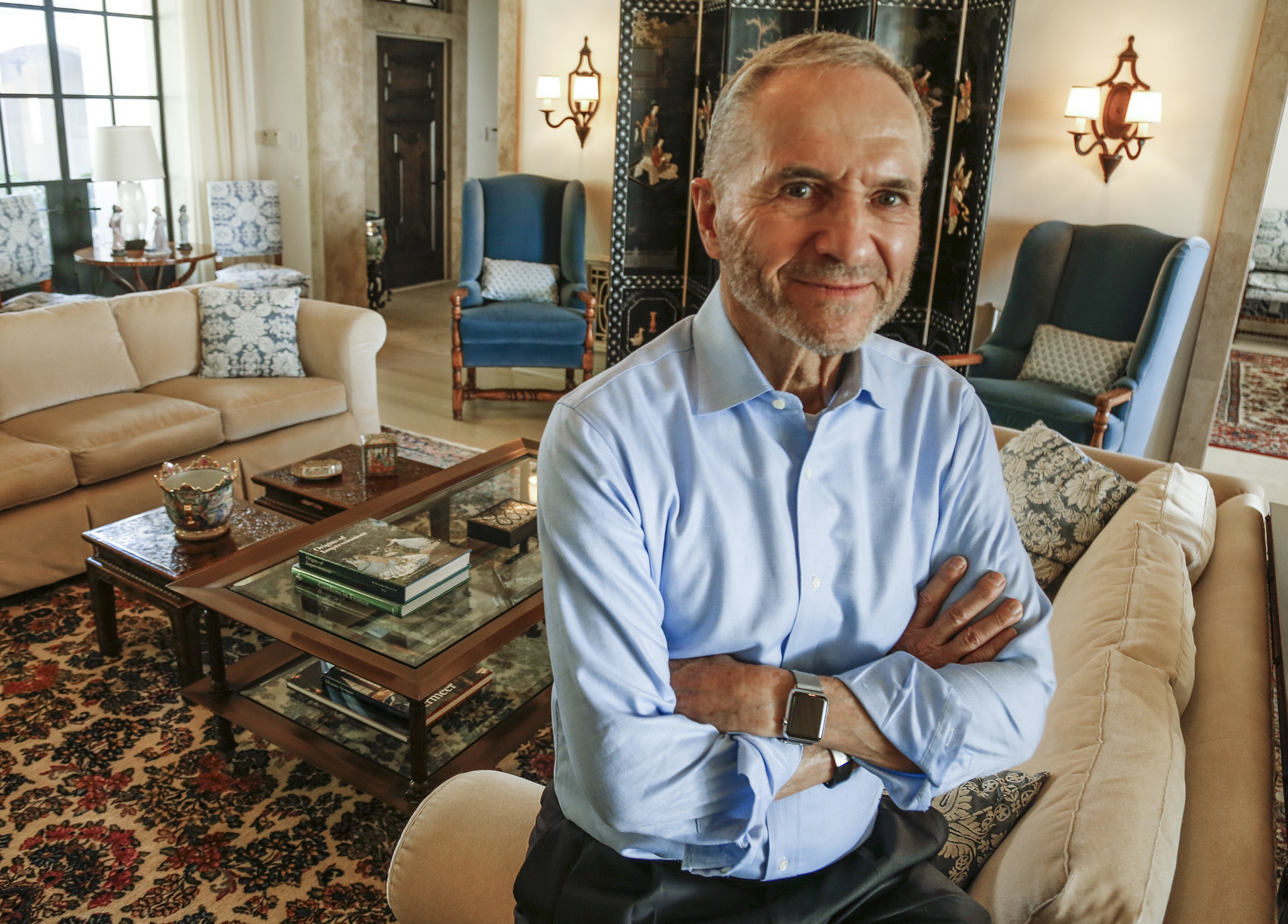

At 84, Ed Thorp is instantly recognizable by his professorial bearing, whip smart dialogue, and a wise twinkle from behind the horn-rimmed glasses.

Studied and unshaken, with the polished look of a Sixties’ salesman, Ed Thorp became the nemesis of the casino industry when he unlocked the next level in “games of chance”.

He’s the man who stripped blackjack -the game of 21- of its mathematical overload, the American roulette of its double-zero advantage, the house of its edge, and the emperor of His Majesty’s clothes when he took on to uncrown Wall Street of its high pretences and expose the financial world as the rigged game of capitalism.

When touched by the harsh, calculated judgements of Edward Thorp, the entire world would unravel like a house of cards: vulnerable to beautiful minds poised on deconstructing the system’s inflated sense of invulnerability.

1. Trust the Math in Blackjack: Where There Are Numbers, There’s a Way

It was the beginning of the 1950s when Ed Thorp descended on Las Vegas, with a hot PhD in mathematics straight out of the oven and his academic research ready to be tried and tested on field.

The house had its own probability calculations based on Cardano’s dice and designed to keep the gamblers at a steady, although indiscernible losing pace.

Ed Thorp managed to circumvent those odds with math that will not be explained here, but that must have looked something like this:

qn = 1 − (q/p) n 1 − (q/p) N

That, by the way, it’s the gambler’s ruin probability equation so when a losing hand falls upon you, you will at least have recognized its metrics.

Ed Thorp could have easily “kept his typewriter shut and milk the blackjack tables”, as a 1964 Life magazine profile on him wittily points out.

Instead, his findings saw light of day in a widely succesful book called “Beat the Dealer”, a gambler’s Bible that ended up being the most requested book in the Las Vegas Public Library.

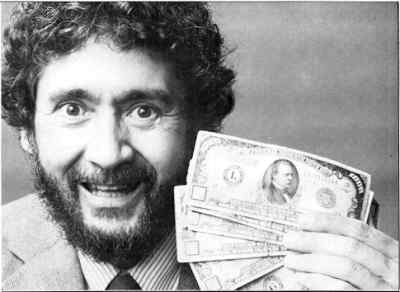

The professor’s apostles were slowly unburdening the casinos of their chips while perceptions about academic figures like Thorp shifted from a mild general snub to rock-star followship.

300 copies of the report were snatched up by the scientific community while Ed Thorp moved on to improving the maths of functional analysis through papers with exotic titles like “Best-Possible Triangle Inequalities for Statistical Metric Spaces” and so on.

Blackjack had been a passing fad and the game, once defeated, no longer posed intellectual challenge or entertainment value. But Thorp’s horizon stretched to higher summits where the champion of the ordinary folk would flex brain muscle with more complex foes: the roulette wheel.

2. Let the Calculator Tally Your Odds: Beating the Roulette with One Big Toe

A tangled mess of cables that must have felt like a particularly annoying pebble in the most famous shoe since Cinderella’s. That was the world’s first wearable computer premiering to inglorious reception at a casino floor in Las Vegas.

Edward Thorp- by then an MIT whizz at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology- and professor Claude Shannon- a WWII code breaker of John Nash quality and the father of information theory were hustler accomplices.

As the final version of the roulette-slayer was wired together in Shannon’s basement lab (didn’t we say they were the rock stars of Silicon Valley?), Thorp couldn’t help but gloss poetically on the meaning of his digital contraption.

“The orbiting roulette ball suddenly seemed like a planet in its stately, precise and predictable path.”

The casino hustler was fishing for the idea of predictability in chaos and must have felt inspired by Einstein’s gravitational matrix and subsequent words “God does not play dice with the universe.”

In 1961, the cigarette pack device along with the shoe and the dangling ear wire (no bluetooth at the time) were tested on ground. The odds were in Thorp’s favor, with an expected gain of 44%.

The device would predict the outcomes of the roulette by calculating the speed and the bouncing rate of the ball.

Thorp would thwart every move made by the casino to break his concentration; he sends shills walking with Oscar-worth acting skills, gulps down the house cocktails with a freeloader’s defiance, endures the wild swings of his frequently diminishing bankroll with the stamina of a boxer absorbing the most ear-splitting upperjaws, and focuses intently on his main strategy.

The Kelly Criterion System, further used by investor giants like Warren Buffet and Bill Gross, is a mathematical betting scheme by which the professor adjusts his bets and risks on the back of precise statistical calculations of his advantage.

As an unsung hero to all those compulsive plungers who had lost fortunes to the house, Ed Thorp waved his magic wound of divine justice- more to the point, a cigarette pack- and brought the casinos to their heels. Or his, if we keep our judgement literal.

3. Wall Street Is Just Another Type of House Edge: Just as Vulnerable to the Risk-Taker

Every game is mathematically designed with a house edge, Thorp discovered. And Wall Street is just another sort of game. Once he beat the casino at its own gamble, the professor used his recently acquired Las Vegas capital to take the road to stock investing.

His first move was to visit the Wall Street library. Surely, someone must have written a book on how to beat the market, maybe? As it turned out, the recipes for stock trends and securities analysis were a shot in the dark, at most.

If the Las Vegas house edge didn’t defeat him, the vast empire that was Wall Street in the 1970s catapulted quite a few big losses in his direction. But Thorp still had an ace up his sleeve: mathematics.

By creating another statistical wonder system to predict stock fluctuations and translating his findings in yet another book, A man for all the Markets, the novice investor developed a pioneering hedge fund called Princeton Newport Partners. Its growing market share meant that soon it would be a place for the high-rollers of Wall Street who could afford to pay a $10 million deposit or get out.

Edward Thorpe: A Hustler of All Games

So why didn’t Ed Thorp make a whole load of money from his gambling pursuits? Or chase the Nobel Prize instead of employing his mathematical formulas to “stick it to the man”?

Maybe because despite the many meanderings along the patterns and lack of patterns that have always shaken the stage curtains from behind, Thorp’s mathematics had always remained a vehicle for social decryption.

“Adam Smith’s market is a whole lot different from our markets. He imagined a market with lots of buyers and sellers of things, nobody had market dominance or could impose things on the market, and there was a lot of competition. The market we have now is nothing like that. The players are so big that they control the levers of financial policy.”, the innovator that disrupted the gambling world theorized in a recent Forbes interview.

The math whizz turned casino hustler/MIT professor/ investor/ business guru/ Silicon Valley legend takes most pride in his social engineering skills. His speculative mind constantly mines for patterns in the generally unchallenged realms of theoretical scientific thought.

Edward Thorp decrypts the wheel of society by employing the same deep-drill calculations that unraveled the secrets of the roulette. Or the blackjack, baccarat or stock trading. These are the places of risk where we ache to go again and again.